We left school in the minibus at seven am. I had no idea where we were going; where the school was, how old the children were, how many of them there would be. On the way we picked up IA, my mentor, and two foreign assistants from another school on the same programme as IA, which was news to me. One of them, as it turned out, was also British. We arrived at Wichian Klinsukon Upattam School, a bustling secondary school on the outskirts of Ayutthaya, shortly before eight, and were immediately shown into their planning room, which looked an awful lot like ours, except that the plastic covered tablecloth was green instead of white. We were given small plastic trays with biscuits and coffee that had so much milk and sugar in it that it took me a moment to realise that’s what it was. WKU School had two foreign assistants, both Indonesian, and from the same programme as IA. They were leading the day, and presented us with a schedule that was a complete departure from the one we had seen yesterday. Thanks to our HM, many of the games and activities had been replaced with ‘cultural rotations’, 20 minute slots in which we were expected to teach the children something cultural from our country. Of course, the HM had mentioned this previously, but not knowing the age or number of children, and what materials would be at my disposal, I had been unable to get further than jotting down a few ideas.

The other two foreign assistants who had come with us were panicked, having no idea what activity they could do. And, as the other British girl put it ‘We have no culture!’ Whilst the Indonesian girls and the Chinese assistant were planning songs, dances, explanations about cultural traditions and dress, we had precisely nothing we could equate to this. There is the National Anthem, but I think it would be quite dull for children, as they would have little idea what they were singing, and in a Buddhist country where the King is much revered, it would seem somewhat disrespectful to teach them to sing ‘God save our gracious Queen’. Fortunately, for me, up some sleeve, I had my iPad, an infinitely useful teaching resource. I now knew that the English Camp was entirely for M1 (12-13) and that I would have six groups of 15-20 pupils, and would teach them all the same thing. I had my flash cards on English breakfast prepared, which I think is a good staple of British culture. I decided to teach them some vocabulary, then, if we were provided with paper (I asked, but had no definite answer), I would blindfold one of them and get the others to instruct them to draw various elements of the English breakfast. If we didn’t have paper, then they would have to mime, which would be challenging (how would you mime bacon?!) but no doubt amusing.

We were led into the school hall, which didn’t seem large enough hold 96 thirteen year olds, as well as numerous teachers and assistants. First teachers and the school’s headmistress gave speeches, and we had numerous photos taken. Then the leading FAs introduced the English Camp rules, which included the following: ‘Campers are expected to follow orders from camp coordinators and their reasonable request. All campers are expected to conduct themselves in a safe manner. Disregard for personal safety and that of others is a ground for disciplinary action’ and ‘Campers should maintain acceptable code of ethics’. Easily understood by all, I’m sure. We began by forming a circle, incorporating every child and FA. Then we sang and danced the Hop! Hop! Hop! song, which I had never heard of before but turned out to be similar to the Hokey Cokey ‘Hop to the right! Hop to the left!’. Once we had performed it a couple of times we were told to form groups of three. Being, I thought, an assistant and not a schoolchild, I helped all those around me who had not understood the instructions to get into groups, only to discover that all the other assistants had simply formed groups with the children. I, along with some other unfortunate kids, was forced into the centre of the circle and ‘punished’ by having to sing a song. I decided to sing Hop! Hop! Hop! as I didn’t want to show off, and wanted to do something the other ‘punished’ children could join in with, but the leading FAs insisted that each child perform individually. Doing all that hopping in front of so many people was not embarrassing, but it did make me wish I’d worn a sports bra. I hoped nobody noticed. We formed the circle again and after this performance I only helped a couple of groups before dashing into a group of my own. It was a relief, because the forfeit the FAs made the children do this time was to spell their names with their bums. I thought this was quite mean for shy thirteen year olds, and the spectators weren’t laughing as much as they would have in England.

Next the children were separated into six groups. Mine had 22, and everyone else’s had 15. It made things more of a challenge, but I think I was popular for being the whitest(!). We were told to come up with a team name and a team cheer. I felt rather at a disadvantage, as the other groups were not only smaller but some of them also had a Thai teacher and a Chinese teacher from the school at their head, but there was no point in whining, I just had to see it as an added challenge and get on with it. I tried to explain to my group that we needed a team name, which resulted in everyone telling me their names. This made for a nice introduction. I realised I was simply going to have to name the team, so I called it ‘Chester’, after my hometown. Then the leaders came round and informed us the name needed to be an animal name, so I named us ‘Fox’; quintessentially British, short, and mildly amusing if mispronounced (everyone pronounced it perfectly all day). There was already some clapping and shouting going on on the other side of the room, so I set about creating our team cheer. I went for the punchy but simple: ‘We’re the best! Beat the rest!’ then added in some clapping and punching the air. Within two minutes all my students had mastered it, and I felt proud when we silenced the rest of the room with our loud, snappy cheer, just during the practice. The other group animals included tiger, elephant and rabbit, all of which had dances miming their animals, which were excellently performed.

The students were then shown a short cartoon about the ASEAN community, narrated in a strange American accent, and a slideshow detailing the name, flag, capital city, motto and National Anthem of each country. I was alarmed when I read that Myanmar’s motto had not been translated, but simply said ‘relates to racial purity’. We then had to play a game, in which the leaders would ask a question, and one child from each team would run to grab a small ratchet, turn it furiously, and answer. The children clearly hadn’t understood, so I suggested all the assistants play one round as an example. For some reason, this resulted in each assistant being shoved by their teams, and having to run for the ratchet, and answer the questions, for almost half the game, until a Thai teacher waded in and said that the students must answer, otherwise what was the point? Already bruised, and mildly peeved that the one time I had managed to get the ratchet the leaders had decided I had mispronounced ‘Vientiane’ when in fact they had misspelt it ‘Viantiane’, I agreed. My team was pretty hopeless, but we did manage to score fifty points in the last round by some miracle. The question changed at the last minute from ‘Mention the ten ASEAN countries’ to ‘Mention the long name of Bangkok’.

It was time for cultural rotations. My activity went better than planned, and I realised it is a method of teaching that could be used to teach many sets of vocabulary, with a slight variation. I began by cycling through the pictures of English breakfast on my iPad, and getting the students to repeat after me. ‘Sausage’ and ‘mushrooms’ presented challenges, but ‘bacon’ was quickly grasped, especially when said in a Jamaican accent, which they loved, and which actually made them pronounce better. Exaggerated expression and emphasis is definitely a way to hold attention. The groups were all mixed level, but some were nevertheless better than others, so with those groups I would teach more vocabulary, and they remembered it more easily when we cycled back through the pictures. I particularly enjoyed hearing them say ‘tea’ and ‘toast’ in a posh English accent, which at first happened by accident, as I forget that my accent is a bit posh and it was only when the words were repeated back to me that I realised what I must sound like! My mentor kept giggling when she could hear the children shouting ‘Bacon! Egg! Bacon!’ from across the room, when I switched faster and faster between the two.

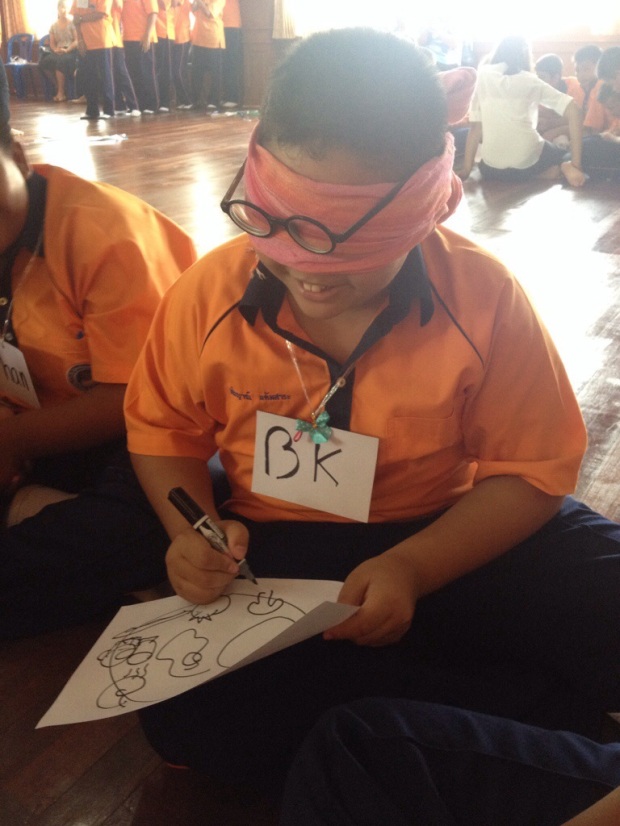

Once the vocabulary was mastered, I would produce a piece of paper (thankfully, there was some) and draw a plate on it, and sometimes a knife and fork. I would then persuade one child to be blindfolded, give them a pen, and get their peers to call out the words we had learnt, to fill the plate up with breakfast. The best groups needed almost no help from me, and I taught them ‘up’ and ‘down’ so that they could better direct the hand of their blindfolded classmate. With other groups I would use the flash cards as a prompt, and try to get them to use the English instead of simply calling out the food in Thai, which happened a couple of times. If the artist had clearly understood everything, I would get them to name everything they had drawn once the blindfold was off and they could laugh at everything they had drawn. I even got a few bright sparks to label the food, spelling it out in English.

I gave every child who drew a sticker, which was a good idea, as it encouraged all the others to try as they all wanted a sticker for their name badge. They all had their nicknames written in English, and some of my favourites included: Beer, Cake, Arm, Pray, Foam and Plug. After our first three rotations I asked the other English girl how her activity (drawing the Union Jack and adding various English pictures) was going, and she said that all the children wanted to do was take selfies with her, get her to autograph their name badges, and add her on Facebook. I also noticed that the leaders were taking selfies with every group they had on their selfie stick. If you don’t know what that is, it’s an extendable rod that people carry round. You stick your camera phone on it and set a timer, then take a selfie. They’re very popular here in Asia. I had some autograph and selfie requests, but brushed them aside until the end of each rotation, if there was time. I also kept my phone hidden so that Facebook was out of sight and mind. There were a few kids, boys especially, who would sit on the fringes of the groups, not participating, but like a big meanie I would bustle over and blindfold one of them, getting their friends to call out the words. After all, one of the camp rules was that all campers must participate.

Exhausted, and with ears ringing from the sound of 96 screeching thirteen year olds all in one room, there was still time for one more game before lunch. It was called ‘More words as many as you can’ and the idea was that the leaders would announce a letter, and the students would have a certain amount of time to write down as many words as they could. The letter was ‘c’ and at first my group drew a blank, so I mimed a cat, and they then managed to come up with car, camp, carrot, cake, cook, can and class, many of which were found around the room or on each others’ name badges. I was proud of my team for coming up with eight words, as they had achieved this with minimal help. I couldn’t see the point of simply telling them words they didn’t know. Unfortunately, we were not all of the same mind, and I was outraged when another group came up with 29 words, all clearly provided by their assistant. I tried to point out, quietly, that this was a little unfair, and was bound to make my group feel stupid, but was told to pipe down. When the 29 words were read out to the rest of the room, my group began to add them to our list, and I made no move to stop them, as we clearly weren’t the only cheaters in the room.

Lunch, a quiet relief, was held in the planning rooms and was an excellent pad Thai, of which I ate one and a half.

For dessert there was watermelon and rambutans. The leaders took us on a tour of the school, which was far larger than ours with several counters in the canteen and even a vending machine. And an ice-cream stand, of which I was envious. There were various verandas where students could relax. I was interested to learn that here the focus was on more traditional academic learning, and in the other two assistants’ school, which was even smaller than ours with only 150 pupils, they also learnt more academic subjects, and no agriculture based ones like in our school. In the bathroom I visited, there were two toilets, one squat but with automatic flush, and the other sitting but with hand flush, neither with paper.

For dessert there was watermelon and rambutans. The leaders took us on a tour of the school, which was far larger than ours with several counters in the canteen and even a vending machine. And an ice-cream stand, of which I was envious. There were various verandas where students could relax. I was interested to learn that here the focus was on more traditional academic learning, and in the other two assistants’ school, which was even smaller than ours with only 150 pupils, they also learnt more academic subjects, and no agriculture based ones like in our school. In the bathroom I visited, there were two toilets, one squat but with automatic flush, and the other sitting but with hand flush, neither with paper.

In the afternoon it was straight back to the extremely loud but at least air-conditioned room, where we did three more rotations. In one, the students blindfolded me, which worked surprisingly well as I could give no vocabulary hints at all. It was reasonably easy to draw blindfolded, and this is an activity I may well use again, on a board instead of with paper. After an hour, there was an unexplained 40 minute break, during which the two leaders disappeared, and the rest of us were left in the room with pumping Thai dance music and 96 children, screaming, fighting and spinning each other around, demanding autographs. Why they couldn’t go outside I simply don’t know. It was almost unbearable. I wanted to reclaim the microphone from the singing children and start performing Heads, shoulders knees and toes, just to calm them down a bit, but it wasn’t my day, or school, so I didn’t want to offend anyone by intervening. My mentor also wanted to wade in, but didn’t dare, so slyly left the room to hide elsewhere. Eventually, one of the student teachers took charge, making everyone sit down, calm down, and sing the English Camp song. This was ‘Oh English Camp, Oh English Camp, Oh English Camp makes me happy. I enjoy English Camp, oh English Camp makes me happy’ to the tune of ‘When the Saints go Marching in’.

The leaders returned, and we played a game called ‘Line up according to’, which meant we each had to get our teams in order, according to their nicknames. I had done mine first, but they kept moving around to stand with their friends, so we lost. Someone produced a small Christmas tree, which they placed in the middle of the room, and everyone was given a heart-shaped card, on which you had to write your comments about English Camp. I wrote good ones, of course, then, much earlier than I expected (it was three) we got back onto the bus and breathed a sigh of relief.

I was dropped at the bus station and boarded a bus for Bangkok, on which I was surprised that it was entirely filled with tourists; Dutch, German, more Dutch and Russian. I was busy chatting when the door slid open, and the last seat was taken by Australian Assistant. We spent the journey discussing the forthcoming English Camp at Saklee, which was news to AA, and the various school gossip (drugs, teenage pregnancies, teacher romances). There’s a lot going on for a small school. In Bangkok we circuited the entirety of Victory Monument, a monument that is also a large roundabout, perhaps equivalent to the Arc de Triomphe, looking for AA’s bus to Pattaya. Every time we came to a stop we had been told it departed from, they pointed us back to the previous one, or on to the next. Eventually, with the help of good old Charlotte, who had come to meet us, we found the right stop, and waited in a large waiting room kitted out with old minibus seats, which were every comfortable. We saw AA onto her bus, then Charlotte and I headed up to Chatachuk market. Although it is supposedly open Friday evenings and all weekend, initially there weren’t many signs of life. We wandered down deserted streets past vendors packing up, eating dinner, or sleeping, and eventually ducked into the market to an open drinks stand. Behind it, we discovered, there were many stalls all open for business, and we began to explore. We emerged onto another street, hidden in the middle, and finally found that the market was happening in certain areas, such as this one. Thailand has an abundance of cheap clothes, with one drawback; most of them are synthetic. With my tendency to get heat rash, this is simply not an option. Thus when presented with an incredible vintage shop, that could easily have been in Paris, my initial excitement turned to disappointment as I realised that everything was synthetic. Still, being me, I made a beeline for what looked like a green silk skirt on the mannequin. It was. Vintage Bally maxi skirt, silk, fully lined, the right size, mine for 100Baht (under £2). Even in Thailand, I am on those bargains. I had dinner (Charlotte watched) at a stall, and was glad that I now knew more or less what all the different dishes were, and was able to choose ones I liked. We suddenly realised it was 11 O’clock at night, and Charlotte needed to be up in six hours to catch a flight. She hadn’t packed yet either. We headed for the exit, only to find it was closed, and so wandered down creepy alleyways of closed stalls looking for a way out. We came back to the same place, and tried to take a different direction, only ending up back at the same closed exit again. We were beginning to wonder whether there was a market lock-in, as there were still plenty of people about, but eventually, we spied the way out. It was so surrounded by people and stalls that it was easy to miss. In the end, Charlotte didn’t sleep, but I couldn’t stay awake much after four. At half five when she left the street was already bustling as though it were midday, with food stalls already open, and people on their way to work or preparing offerings for the monks.